The good fortune of Denison, Iowa, and the bad fortune of Plainview, Texas, demonstrate the difference between the cattle haves and have-nots.

A tale of

two cities

It took a couple phone calls for the reality of Cargill’s decision to set in on Kevin Carter. As director of economic development efforts in Plainview, Texas, losing the community’s largest employer, with 2,000 people on its payroll, made his job that much harder.

“It’s a tough blow when you lose that many jobs,” he says, peering out his office window to Route 70.

For Brad Bonner, it was a welcome surprise to get a phone call from a reporter asking about anything other than a recent double homicide on a farm that had shaken Denison, Iowa. The town’s mayor was more than happy to talk some good news: Tyson Foods had decided to keep open its local beef slaughterhouse, and 380 folks were keeping their jobs.

“Relief” was the first word that came to his mind.

The contrast between these two meatpacking towns demonstrates the human side of a shift in the cattle industry, exacerbated by extreme drought conditions, that is making the Midwest a more reliable place to operate a slaughterhouse.

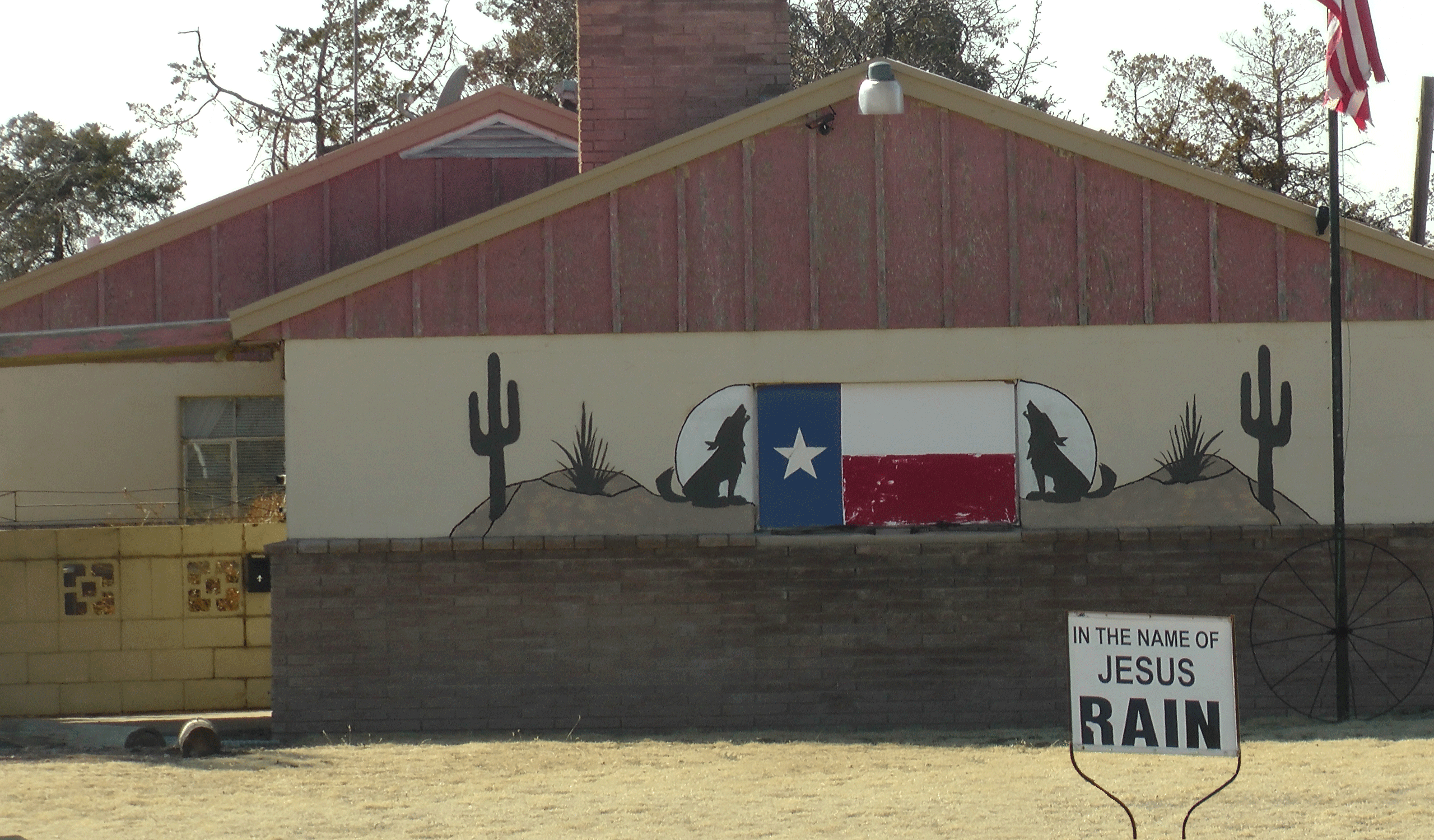

Kevin Carter, director of economic development for Plainview, Texas, discusses the local impact from the idling of Cargill’s local beef slaughterhouse, which employed more than 2,000 people in the area. Tough times are apparent in the dilapidated facades of homes and churches, but Carter isn’t giving up hope as the city searches for alternative sources of revenue.

The Plainview plant’s displaced workers account for some 13 percent of Hale County’s workforce, and the loss of 2,000 jobs includes an estimated loss to that and surrounding counties of more than $865 million in gross sales and $60 million in labor income from the plant alone, according to a study by Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. That’s to say nothing of the indirect (reduced business-to-business sales) and induced (less household spending) effects of the plant closure.

Life sure looks tough in Plainview as it is, unless empty lots, abandoned churches, peeling paint and plywood-boarded windows in the neighborhoods surrounding its downtown are en vogue. A year after the closure, the decay can’t be blamed solely on the idled packing plant, but it certainly isn’t a harbinger of prosperity to come.

Life sure looks tough in Plainview as it is, unless empty lots, abandoned churches, peeling paint and plywood-boarded windows in the neighborhoods surrounding its downtown are en vogue.

Some 200 to 250 of the Plainview plant’s workers now work in other Cargill plants, mostly in the Friona facility about 75 miles away. They catch a shuttle to and from the Plainview plant. Another 400 to 500 qualified for retirement packages. Nearly 225 likely left Plainview altogether (based on school enrollment records, Carter says) and about 500 are still unemployed. (The remainder are not on unemployment rolls and are considered employed.)

Iowa has seen an influx of cattle due to its reliable corn supply. Photo credit: Shutterstock

“The crazy thing about it is we didn’t lose revenue [last year],” Carter says. “Sales tax was up 1.2 percent last year, which is unbelievable considering having that big of a loss of jobs."

Unemployment benefits have helped. But according to the AgriLife study, Plainview stands to lose a little over $1 million in sales taxes, or about 10 percent of total revenues (according to city budget documents), as a result of reduced business activity that had been provided by the Cargill plant.

In Denison, 860 miles northeast of Plainview, the town’s officials were looking at similar gloom with the threat over the last two years that Tyson Foods might close the local slaughterhouse, also in response to tight cattle supplies. But in March, Tyson decided to keep the plant open as conditions have improved, including more cattle availability.

Although a happier story has unfolded in Denison, Bonner said it surely could have gone differently. “To have the threat of [Tyson] leaving, even just from a morale standpoint, was a blow,” he says.

Denison revolves around meatpacking; the modern area of mega-plants is known to have begun there in the early 1960s by Iowa Beef Packers, which became IBP before it was acquired by Tyson in 2001. The city also is home to Farmland Foods, Appa Fine Foods and Premium Protein. It has called itself the “Capital of the Meat Empire.”

Closure of Tyson’s local beef plant “definitely would have had a strong negative impact, not only on the urban side with the jobs and people living here but also on our herds,” Bonner says. “Part of the reason the plant is there is because we have the herds to feed it.”

It’s a tough blow when you lose that many jobs.

For the same reason, say 48 million of its dollars, Iowa Premium Beef in October will be reopening a plant in Tama, Iowa. The facility, closed since 2004 when a venture called Iowa Quality Beef failed, is slated to initially slaughter 1,100 head per day and eventually double that volume, according to industry analyst Steve Kay, who wrote in BEEF Magazine that the new plant will generate more corn finishing in Iowa.

The state had 670,000 head on feed in feedlots of at least 1,000 head on April 1, up 6.3 percent from the year-earlier figure. As for feedlots with fewer than 1,000 head, Iowa had 73,000 of them that marketed 3 million head in 2013, up 5.5 percent from 2012. “This indicates that a lot more cattle are being fed in small feedlots in the Corn Belt,” Kay wrote.

Iowa meatpacking towns might be better off for now than some in the Southern Plains, but Bonner calls the potential closure of Tyson’s Denison beef plant a “wake-up call” for the city. The future of meatpacking there is not guaranteed, he says, and his town needs to be more proactive in engaging its local businesses and working to keep them there.

Back in Plainview, Carter expects the biggest financial impact going forward for the city will be the loss of water revenue. Cargill paid roughly $1 million per year for city water.

Plainview’s not going to run out of water any time soon, but the city is conscious of the long-term possibilities, and has secured through Texas’s Canadian River Municipal Water Authority ground water rights projected to last beyond the end of this century. The city also has implemented a multi-tiered water rate structure with increasing rates to encourage conservation among its constituents.

Wind energy in the Texas Panhandle offers an alternative source of income to meatpacking towns such as Plainview, where Cargill idled its beef slaughterhouse early last year. Photo credit: Shutterstock

Carter says his department, meanwhile, is trying to recruit non-water-using businesses, particularly wind energy companies. Last year Hale (County) Community Energy announced plans to erect upwards of 650 wind turbines in the area, which is one of the windiest regions in the United States: Amarillo and Lubbock respectively rank 6th and 17th in the nation’s top 25, according to U.S. government data.

Carter said upcoming wind projects will help create jobs, but they won’t generate the amount of jobs that Cargill’s local slaughterhouse did.

“I think everybody would like to see it open in some capacity,” he says. “When we met with Cargill, Mr. [Cargill Beef President John] Keating said if that happened, it’d probably be a five- to six-year event, provided that the herd comes back.”

Says Keating, “Regarding the Cargill beef processing facility in Plainview, what we said last year has not changed — we do not see the cattle supply improving for a number of years and the plant remains idle.”

Although aware of the packing industry’s overcapacity condition, Carter, who worked at the Plainview plant during and after college, isn’t giving up hope that it will reopen.

“It’s always a possibility,” he says.

The final chapter will cover the future outlook for the Texas beef industry and the proud people who make it work. What's next?